The Harlem Renaissance was more than a literary movement—it was a cultural explosion that reshaped how America understood Black identity, creativity, and citizenship. Between 1924 and 1929, writers, musicians, and artists in one New York City neighborhood put Black culture on a national and international stage, creating work that still resonates nearly a century later.

The movement drew people from the South and the Caribbean who transformed Harlem into the undisputed “Negro capital of America.” Magazines like The Crisis and Opportunity amplified their voices, connecting artists with publishers and building an infrastructure that turned creative achievement into a platform for civil rights advocacy .

This guide explores the forces that built Harlem, the ideas that powered the movement, and the lasting legacy that continues to shape American art and political debate. From Langston Hughes to the Cotton Club, from economic empowerment to the fight for representation, we examine how a single neighborhood transformed itself—and, in doing so, transformed the nation.

Key Takeaways

- The era framed a defining 20th century movement anchored in new york city.

- Artists and writers forged modern identity through music, theater, and letters.

- Migration from the South and Caribbean fueled dynamic cultural exchange.

- Economic empowerment, publishing, and nightlife amplified voices and markets.

- Legacy ties to later civil rights debates and today’s discussions about equity.

Harlem Renaissance Black History: What It Was And Why It Matters

From the end of World War I through the mid-1930s, Harlem hosted an extraordinary flowering of African American culture known as the Harlem Renaissance. Writers, artists, musicians, and thinkers asserted their right to define Black identity on their own terms, creating work that still resonates today.

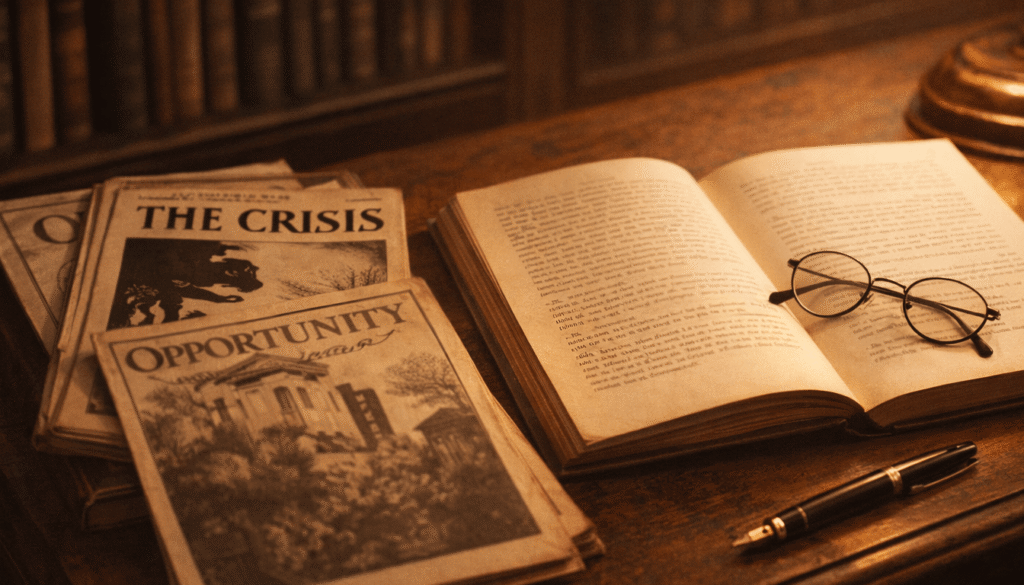

Centered in New York but spreading through national networks, the movement—called the “New Negro” movement by participants—rejected degrading stereotypes and insisted on complex, dignified portrayals of Black life . Magazines like The Crisis and Opportunity provided essential platforms, connecting writers with publishers and creating a national conversation about Black art and politics .

What Was It?

The Harlem Renaissance was an assertion of cultural self-determination. For the first time on a national scale, Black artists and intellectuals collectively took control of their own representation . Through literature, visual art, music, and theater, they challenged America to see Black life as worthy of serious artistic exploration.

Why It Matters

The movement established that Black artists could shape American culture on their own terms, creating a template for everything from the Black Arts Movement to hip-hop . It also laid essential groundwork for the civil rights movement, refining organizational practices—churches as gathering spaces, community mobilization—that would prove crucial in later decades .

Timeline

- Late 1910s: Great Migration creates concentrated Black communities with economic and cultural critical mass

- 1924: Opportunity awards dinner connects Black writers with white publishers

- 1925: Alain Locke publishes The New Negro, canonizing the movement’s literary achievements

- 1920s: Peak flowering of jazz, literature, and visual art

- 1929: Great Depression begins eroding economic support for artists

- 1935: Harlem Riot marks transition from cultural celebration to political protest

The New Negro Defined

Alain Locke’s 1925 anthology gave the era its defining concept: a break with the past, a rejection of stereotype, and an embrace of self-confidence, intellectual rigor, and political awareness . This new identity found expression in every medium—Langston Hughes’s poetry, Aaron Douglas’s visual art, Duke Ellington’s music—creating a distinctly African American aesthetic that still influences artists today.

From Reconstruction To Great Migration: The Forces That Built Harlem

A mix of legal disfranchisement, crop failures, and new job openings pushed thousands to seek a safer urban life in the early twentieth century. After Reconstruction, southern voting bans and Jim Crow laws (c. 1890–1908) drove many African Americans to look for rights and safety elsewhere, setting in motion the Great Migration that would transform Northern cities and create the conditions for the Harlem Renaissance.

Disfranchisement, Jim Crow, and the Search for Rights

Violence and legal exclusion made migration a civic tactic as much as an economic one. From the 1890s forward, Southern states systematically stripped African Americans of the right to vote through poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses. Lynchings and race riots made clear that the federal government would not intervene to protect Black lives or rights. Families left the South not merely for better wages but to claim basic protections and steady work in Northern cities where the rule of law applied more evenly—though still imperfectly—to all citizens .

Real Estate Shifts and the Making of a Black Mecca

Real estate entrepreneurs changed the local map of New York City. Philip A. Payton Jr.’s Afro-American Realty Company (1903) fought housing discrimination directly, renting and purchasing properties that white landlords refused to offer to Black tenants. Payton’s aggressive strategy—acquiring leases on white-owned buildings and then renting to Black families—broke through residential barriers and helped create new tenancy options for arriving migrants .

A pivotal 1910 block purchase on 135th Street and Fifth Avenue by Black realtors and St. Mark’s Methodist Episcopal Church accelerated demographic change. This transaction opened a concentrated stretch of housing to Black residents at a moment when thousands were arriving, creating the geographic core of what would become Black Harlem. The St. Mark’s purchase was not merely a real estate deal; it was an institutional commitment that signaled to the broader community that Harlem was becoming a Black space .

Economic Opportunity and Labor Demand

World War I fundamentally shifted the economic landscape. The war halted European immigration, cutting off the flow of cheap labor that had powered Northern industry for decades. Northern factories, suddenly desperate for workers, sent labor recruiters into the South for the first time. For African Americans trapped in sharecropping and debt peonage, these jobs offered a path out .

The wartime demand for industrial labor coincided with agricultural catastrophe. The boll weevil infestation devastated cotton crops across the South, wiping out the already meager earnings of Black sharecroppers and tenant farmers. Crop failures and floods in the 1910s intensified departures from rural areas, pushing hundreds of thousands toward Northern cities where at least factory jobs promised steady wages .

Caribbean Influences and Transatlantic Currents

Wartime labor demand and fewer European arrivals expanded jobs not only for African Americans but also for Caribbean migrants, who arrived in growing numbers during this same period. By 1930, approximately one-quarter of Harlem’s residents came from the West Indies, bringing distinct languages, political traditions, and cultural practices that reshaped the movement and world of ideas .

These immigrants, concentrated in Harlem but maintaining ties to their home islands, added a transnational dimension to Black New York. Figures like Claude McKay, Marcus Garvey, and Hubert Harrison drew on Caribbean experiences of colonialism and resistance, contributing perspectives that both complemented and challenged African American leadership. The Caribbean presence ensured that Harlem’s identity was not simply a Southern Black culture transplanted North but a meeting ground for the broader African diaspora .

For a broader context, see a concise Harlem Renaissance overview that traces how migration tied to a 20th century urban shift across the globe.

Key Ideas of the Harlem Renaissance: The New Negro and Cultural Pride

Intellectual leaders of the Harlem Renaissance turned creative excellence into a strategy for social change. The “New Negro” idea—championed by philosopher Alain Locke—tied artistic achievement to civic standing, arguing that representation could reshape public opinion more effectively than political rhetoric alone .

Alain Locke’s Vision And The Crisis Of Representation

Alain Locke’s Vision. Locke’s landmark anthology The New Negro (1925) urged artists to pursue excellence as a form of advocacy. He called for a “racial idiom” in Black art—work that drew on African aesthetics and Black folk traditions while speaking to universal human experiences. The NAACP’s The Crisis and the Urban League’s Opportunity amplified these voices, placing Black writers before national audiences and building the case for full citizenship through cultural achievement .

Two Rival Paths. The era’s most significant intellectual debate pitted W.E.B. Du Bois against Marcus Garvey. Du Bois, through the NAACP, advocated for integration, litigation, and the leadership of an educated elite. Garvey’s UNIA built a mass movement around racial pride, economic self-sufficiency, and the dream of African return .

Their conflict was bitter—Du Bois called Garvey “the most dangerous enemy of the Negro race in America”; Garvey dismissed Du Bois as a “white man’s Negro”—but both were pan-Africanists who understood Black freedom as a global question . Their rivalry framed debates over integration vs. separatism, elite vs. mass leadership, and American identity vs. diasporic consciousness that would echo through the civil rights movement and beyond.

Major Writers of the Harlem Renaissance: Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and Their Circle

The writers of the Harlem Renaissance transformed American literature by reworking Black speech, song, and folklore into modern literary forms. Their work was simultaneously artistic achievement and social argument—proof that Black life was worthy of serious literary exploration.

Langston Hughes and Jazz Poetry

No writer better captured the era’s spirit than Langston Hughes. He pioneered jazz poetry, translating blues and jazz rhythms into verse. His 1926 collection The Weary Blues demonstrated this fusion, and his landmark essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain” declared artistic independence: “We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame” . Hughes became the leading voice for a generation of writers committed to authentic Black expression.

Zora Neale Hurston: Voice of the Folk

Trained as an anthropologist at Barnard College under Franz Boas, Zora Neale Hurston traveled the South collecting Black folklore, songs, and stories. This training shaped fiction that celebrated vernacular Black life without apology. Stories like “Sweat” (1926) and “The Gilded Six-Bits” (1933) rendered Black dialect and rural experience with authenticity. Though sometimes criticized by male intellectuals who saw folklore as backward, Hurston’s commitment to vernacular voice proved lasting. Her 1937 novel Their Eyes Were Watching God is now recognized as an American masterpiece .

Literary Gatekeepers and the New Negro Anthology

Alain Locke’s landmark anthology The New Negro (1925) canonized the movement’s literary achievements, featuring Hughes, Hurston, Countee Cullen, Claude McKay, and Jean Toomer . Behind the scenes, editors shaped which writers gained recognition. Jessie Redmon Fauset, literary editor of The Crisis from 1919 to 1926, discovered and nurtured numerous writers—one scholar notes she “midwifed the Harlem Renaissance into being” . Charles S. Johnson of Opportunity magazine performed a similar role; his 1924 Civic Club dinner connected Black writers with white publishers, dramatically expanding opportunities .

The Networks That Sustained a Movement

Magazines, salons, and readings formed circulation networks that kept writers connected and ideas alive. The Crisis and Opportunity sponsored literary prizes that provided both recognition and much-needed income. Salons hosted by figures like A’Lelia Walker, daughter of hair-care entrepreneur Madam C.J. Walker, brought writers, artists, and patrons together in informal settings where ideas could circulate freely .

Not all writers sought the approval of established gatekeepers. In 1926, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and Wallace Thurman launched Fire!! magazine as a deliberate challenge to respectability politics. Though only one issue appeared, it signaled a generational shift—younger writers insisted on representing Black experience in all its complexity, rejecting what they saw as the overly decorous literature of their predecessors .

These networks were essential infrastructure. They provided not only publication opportunities but community—a sense that writers were part of something larger than themselves, engaged in a collective project to reshape American culture.

For more on how art and literature connected to broader currents, see a focused perspective at Harlem Is Everywhere: Art and Literature.

The Sound of the Harlem Renaissance: Jazz, Blues, and the Musicians Who Defined an Era

Music was the most accessible and widely consumed art form of the Harlem Renaissance. While literature reached readers through magazines and books, jazz and blues poured out of nightclubs, rent parties, and recording studios, reaching audiences across racial and geographic boundaries. The era’s musicians transformed American music, elevating vernacular forms into sophisticated art while never losing connection to the communities that created them.

Harlem Stride Piano and the Club Scene

In the 1920s, Harlem’s nightlife revolved around pianists who developed a distinctive style known as stride. Named for the left hand’s “striding” motion—alternating between bass notes and chords—stride piano demanded extraordinary technical skill and creativity. Its practitioners transformed pianos into one-man orchestras, capable of filling clubs with sound and energy .

James P. Johnson essentially invented the style. His 1921 composition “Carolina Shout” became a test piece that every aspiring Harlem pianist had to master. Johnson trained and influenced a generation of players, including his protégé Fats Waller, whose virtuosity and showmanship made him one of the era’s most beloved figures. Waller’s compositions, including “Ain’t Misbehavin'” and “Honeysuckle Rose,” became jazz standards that remain in the repertoire today .

These pianists anchored Harlem’s rent party culture. When residents needed money for rent, they’d invite neighbors to late-night gatherings featuring food, drink, and music. Stride pianists provided entertainment while building a competitive, creative community that pushed the music forward.

Duke Ellington at the Cotton Club

No musician better represents the complexity of the Harlem Renaissance than Duke Ellington. From 1927 to 1931, Ellington and his orchestra held residency at Harlem’s most famous (and infamous) nightspot, the Cotton Club. Though the club excluded Black patrons—catering instead to white audiences seeking exoticized entertainment—Ellington used the venue’s national reach to broadcast his music weekly over the radio .

Ellington rejected the label “jazz,” preferring to call his work “American music.” His compositions, including “Mood Indigo,” “Sophisticated Lady,” and “It Don’t Mean a Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing),” demonstrated that dance music could also be serious art. He collaborated closely with his band members, particularly trumpeter Bubber Miley and clarinetist Barney Bigard, incorporating their distinctive sounds into compositions that showcased individual voices within ensemble textures .

Ellington’s achievement was twofold. He proved that Black composers could create sophisticated, extended works worthy of concert halls. And he demonstrated that commercial success and artistic ambition were not mutually exclusive.

Louis Armstrong and the Birth of the Solo

While Ellington worked in New York, Louis Armstrong arrived from Chicago in 1924, already transforming jazz. Armstrong’s genius lay in his melodic inventiveness and technical brilliance. Before Armstrong, jazz was primarily ensemble music; after him, the soloist took center stage .

Armstrong’s recordings with his Hot Five and Hot Seven, made between 1925 and 1928, revolutionized the music. His improvised solos on tracks like “West End Blues” and “Potato Head Blues” demonstrated that jazz could achieve the emotional depth and formal sophistication of European classical music while remaining rooted in African American vernacular expression .

Though he left New York for Chicago and later toured internationally, Armstrong’s influence on Harlem musicians was profound. Every jazz musician who followed absorbed his innovations.

From Spirituals to Concert Halls

Not all Renaissance musicians worked in popular forms. Composers William Grant Still and Florence Price bridged Black vernacular traditions and European classical music. Still’s Afro-American Symphony (1930) became the first symphony by an African American composer performed by a major orchestra. Price’s Symphony in E Minor (1932), premiered by the Chicago Symphony, drew on spirituals and folk melodies. Together, they proved that Black musical traditions could sustain the largest forms of Western art, challenging assumptions about racial capacity and cultural achievement .

The Blues Women

While male instrumentalists dominated jazz, women singers carried the blues. Bessie Smith, the “Empress of the Blues,” recorded extensively for Columbia Records and became the highest-paid Black performer of her era. Her recordings, including “Downhearted Blues” and “St. Louis Blues,” sold hundreds of thousands of copies to Black audiences who heard their own experiences in her voice .

Smith and her contemporaries—including Ma Rainey, Ethel Waters, and Clara Smith—sang of love, loss, travel, and independence. Their lyrics spoke directly to Black women’s experiences in ways that literature and visual art rarely did. They were not only entertainers but cultural representatives, giving voice to communities that otherwise went unheard in national media .

Economics, Opportunity, and Institutions: Building Black Empowerment

Economic networks and cultural institutions worked together to turn creative labor into steady work and public influence. Without this infrastructure, the Harlem Renaissance would have remained a scattering of individual talents rather than a coordinated movement.

The Black Press and Publishing Pipeline

Opportunity magazine’s 1924 Civic Club dinner exemplified how institutions shaped careers. That single event connected writers with white publishers and opened pipelines that had been systematically closed. The Crisis, edited by W.E.B. Du Bois, and The Negro World, published by Marcus Garvey’s UNIA, performed similar work—amplifying voices, publishing new work, and shaping public conversation around Black art and politics .

Small presses, salons, and local venues created markets and training networks where none had existed. Entrepreneurs organized clubs and small publishing operations that sustained careers between major breakthroughs. This ecosystem, however fragile, provided the material conditions for artistic production.

Patronage, Philanthropy, and Access

White patrons, including photographer Carl Van Vechten, opened doors to publishers and galleries but raised persistent questions about control and authenticity. Van Vechten promoted numerous Black writers and artists, yet his fascination with primitivism and his willingness to use racial epithets in private correspondence revealed the complexities of cross-racial patronage .

Museums and mainstream galleries largely excluded Black artists throughout the 1920s. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) of the 1930s, though arriving after the Renaissance’s peak, later provided funding, training, and exhibition space that partially addressed these gaps .

| Institutional Channel | Primary Actors | Benefit | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black Press | The Crisis, Opportunity, Negro World | Publicity, careers for writers | Limited national reach early on |

| Patronage | Carl Van Vechten, private donors | Gallery access, introductions | Conditional support, gatekeeping |

| Public Programs | WPA arts projects | Funding, training, exhibition space | Temporary, uneven selection |

Decline of the Harlem Renaissance: Causes and Context

The Great Depression’s Economic Toll

The 1929 stock market crash delivered a devastating blow to the Harlem Renaissance. By the mid-1930s, writers had shifted from celebrating Black culture to documenting breadlines and unemployment. Harlem suffered acutely—at one point, approximately 50 percent of its employable residents were out of work . Organizations like the NAACP and Urban League shifted from cultural patronage to economic survival. Patrons and publishers withdrew support, nightclubs closed, and the flourishing scene of the 1920s could not withstand the Depression’s devastation .

How Migration Changed Harlem

As the Depression deepened, key figures departed. Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, Charles S. Johnson, and W.E.B. Du Bois all left New York in the early 1930s, most relocating to France . Meanwhile, Southern African Americans and Puerto Ricans continued arriving, straining limited resources and altering Harlem’s character. The optimistic spirit that fueled the Renaissance gave way to the grim realities of poverty .

The Harlem Riot of 1935

On March 19, 1935, a 16-year-old Puerto Rican boy was caught stealing a penknife. When rumors spread that he had been beaten to death, simmering frustrations exploded. For two days, rioters targeted white-owned businesses along 125th Street, causing $2 million in property damage. Three Black people died, more than 100 were injured, and 125 were arrested .

The riot held profound significance. Historian Jeffrey Stewart called it “the first modern race riot,” symbolizing that “the optimism and hopefulness that had fueled the Harlem Renaissance was dead” . Cultural celebration gave way to protest against racial and economic injustice.

Why the Movement Ended

The Harlem Renaissance did not vanish overnight—nearly one-third of its books appeared after 1929 . Its decline resulted from converging forces: economic collapse, the departure of key figures, demographic shifts, and the 1935 riot that shattered Harlem’s image as the optimistic “Mecca” of the New Negro . By the mid-1930s, social realism had replaced modernism as the dominant artistic mode, and the focus shifted from celebrating Black culture to documenting social conditions .

Yet even as the movement faded, its achievements resonated. The Harlem Renaissance permanently transformed American culture and established a legacy that would inspire generations of artists and activists to come .

Decline of the Harlem Renaissance: Factors, Effects, and Consequences

| Factor | Immediate Effect | Long-Term Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Economic | Venue closures, loss of arts patronage, soaring unemployment in Harlem (50% by mid-1930s) | Permanent decline in arts funding; organizations shifted focus from culture to economic survival |

| Demographic | Exodus of key figures (Hughes, Johnson, DuBois); continued influx of poor migrants | Loss of creative leadership; increased strain on community resources |

| Political | 1935 Harlem Riot; $2 million in property damage; shattered image of Harlem as cultural “Mecca” | End of Renaissance optimism; rise of protest era and social realism in art |

| Institutional | NAACP and Urban League shifted priorities from arts to economics; WPA relief projects began | Art became tool for social documentation rather than cultural celebration; uneven recovery |

Why the Harlem Renaissance Still Matters

The Harlem Renaissance was more than a 1920s literary movement—it was a cultural awakening that reshaped how America understood Black identity, creativity, and citizenship. Nearly a century later, its echoes remain visible across American culture .

A Political and Social Foundation

The movement laid essential groundwork for the civil rights movement. Organizational practices refined during the Renaissance—using churches as gathering places, mobilizing communities, understanding the power of collective action—became essential tools in the 1950s and 1960s . The NAACP’s 1917 Silent Protest Parade, where ten thousand African Americans marched silently down Fifth Avenue, prefigured the mass demonstrations of the civil rights era .

Cultural Transformation

The Renaissance permanently transformed American culture. Jazz and blues, elevated from regional expressions to national art forms, continue to shape music from rock to hip-hop . Writers like Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston established themes of racial identity and resilience that still resonate in contemporary literature. Visual artists like Aaron Douglas created a distinctly African American aesthetic tradition by synthesizing European modernism with West African art—a visual language that continues to influence design and illustration today .

The Power of Self-Definition

At its core, the Renaissance was about Black people taking control of their own representation for the first time on a national scale. As Langston Hughes declared, “We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame” . This assertion—that Black artists had the right to define themselves, tell their own stories, and claim their place in American culture—was itself a revolutionary political act .

The movement’s legacy endures because the questions it raised about identity, representation, and cultural ownership remain as urgent as ever. When contemporary artists grapple with how to represent Black life authentically, they engage in a conversation that began in the salons and nightclubs of 1920s Harlem .

The Harlem Renaissance: A Legacy That Lives On

The Harlem Renaissance was many things: a literary movement, a musical revolution, a visual arts awakening, and a political assertion of Black humanity. But above all, it proved that a community could transform itself through culture.

In little more than a decade, the writers, artists, and thinkers of Harlem created work that redefined American art while building institutions—The Crisis, Opportunity, the studios of Savage and Douglas—that turned individual achievement into collective movement. They grappled with real limitations: an economy that collapsed with the Great Depression, demographic shifts that changed Harlem’s character, and a 1935 riot that shattered the optimism of the “New Negro” era. Yet they left behind something enduring.

The organizational practices refined during these years became tools for the civil rights movement. The art itself never disappeared, rediscovered by each generation. And the questions the Renaissance raised—about identity, representation, and the power of self-definition—remain as urgent as ever.

The Harlem Renaissance matters because it showed what was possible: that creativity, organized and sustained, could challenge hierarchies and reshape a nation’s culture. Its work still speaks to us across the decades—a continuing assertion of presence, dignity, and the transformative power of art. That light, first kindled in the salons and nightclubs of 1920s Harlem, still burns.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Harlem Renaissance

What was the New Negro movement and why did it matter?

The New Negro movement promoted racial pride, artistic expression, and political self-determination among African Americans in New York City and beyond. It mattered because it reframed Black identity in the early 20th century, boosted careers for writers, musicians, and artists, and influenced civil rights organizing by asserting cultural and economic claims to equality.

Which writers and artists defined this period?

Key figures included Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Aaron Douglas, Augusta Savage, William Grant Still, Duke Ellington, and James VanDerZee. They produced influential literature, visual art, music, and photography that shaped national and transatlantic views of Black life and creativity.

How did the Great Migration shape cultural life in New York City?

The Great Migration brought large numbers of Black Americans from the rural South to northern cities. This demographic shift created dense Black urban communities, expanded markets for Black-owned businesses and arts venues, and fostered networks that supported new cultural production and political activism.

What role did jazz and blues play in the movement?

Jazz and blues provided a sonic language for modern Black identity. Clubs and performance halls nurtured innovation in rhythm, improvisation, and ensemble forms. Musicians like Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington helped move Black music from local stages to national prominence and influenced poetry and prose forms.

How did organizations like the NAACP and UNIA influence debates?

The NAACP and the Universal Negro Improvement Association offered contrasting strategies. The NAACP pushed legal challenges and integrationist reforms, while Marcus Garvey’s UNIA emphasized economic self-help and Black nationalism. These debates shaped intellectual life and political priorities in the era.

In what ways did visual artists incorporate African aesthetics?

Artists such as Aaron Douglas used African motifs, stylized forms, and mural techniques to connect contemporary Black experience with pan-African traditions. That visual language reinforced ideas of dignity, historical continuity, and artistic modernism.

What economic forces supported and constrained the movement?

Black entrepreneurship, Black-owned newspapers, and philanthropic patrons offered crucial funding and distribution channels. At the same time, residential segregation, discriminatory lending, and later the Great Depression limited resources and contributed to the movement’s decline.

How did the Cotton Club and other nightlife venues affect perceptions of Black culture?

Nightlife venues popularized Black music and dance but often presented sanitized or segregated performances for white audiences. They created cultural visibility and economic opportunity but also raised tensions about exploitation and representation.

What caused the decline of the movement in the 1930s?

Economic collapse during the Great Depression, shifts in migration patterns, and reduced patronage weakened institutions. The 1935 Harlem riot reflected mounting frustrations over work, housing, and police treatment, signaling the end of the era’s high cultural visibility.

How did the movement influence later civil rights and cultural change?

The era forged artistic lineages and organizational models that fueled mid-century activism. It reshaped national conversations about rights, identity, and representation and informed later movements for racial justice and Black cultural pride across the United States and the diaspora.

What primary sources are best for studying this period?

Important primary sources include The New Negro anthology, issues of The Crisis and Opportunity magazines, recordings by performers of the time, and photographs by James VanDerZee. Archives, letters, and contemporary reviews also offer direct insight into ideas and reception.

How did Caribbean migration and transatlantic ties influence cultural production?

Caribbean immigrants brought musical rhythms, religious practices, and political ideas that enriched local scenes and connected New York to broader diasporic currents. Figures with Caribbean roots contributed to literary debates and community institutions, expanding stylistic and political horizons.